Snowball Earth’s Liquid Seas Dipped Way Below Freezing

Earth froze over 717 million years ago. Ice crept down from the poles to the equator, and the dark subglacial seas suffocated without sunlight to power photosynthesis. Earth became an unrecognizable, alien world—a “snowball Earth,” where even the water was colder than freezing.

In Nature Communications, researchers reported the first measured sea temperature from a snowball Earth episode: −15°C ± 7°C. If this figure holds up, it will be the coldest measured sea temperature in Earth’s history.

For water to be that cold without freezing, it would have to be very salty. And indeed, the team’s analysis suggests that some pockets of seawater during the Sturtian snowball glaciation, which lasted 57 million years, could have been up to 4 times saltier than modern ocean water.

“We’re dealing with salty brines,” said Ross Mitchell, a geologist at the Institute of Geology and Geophysics of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. “That’s exactly what you see in Antarctica today,” he added, except that snowball Earth’s brines were a bit colder than even the −13°C salty slush of Antarctica’s ice-covered Lake Vida today.

Past Iron

The Sturtian snowball was a runaway climate catastrophe that occurred because ice reflects more sunlight than land or water. Ice reflected sunlight, which cooled the planet, which made more ice, which reflected more sunlight and so on, until the whole world ended up buried under glaciers that could have been up to a kilometer thick.

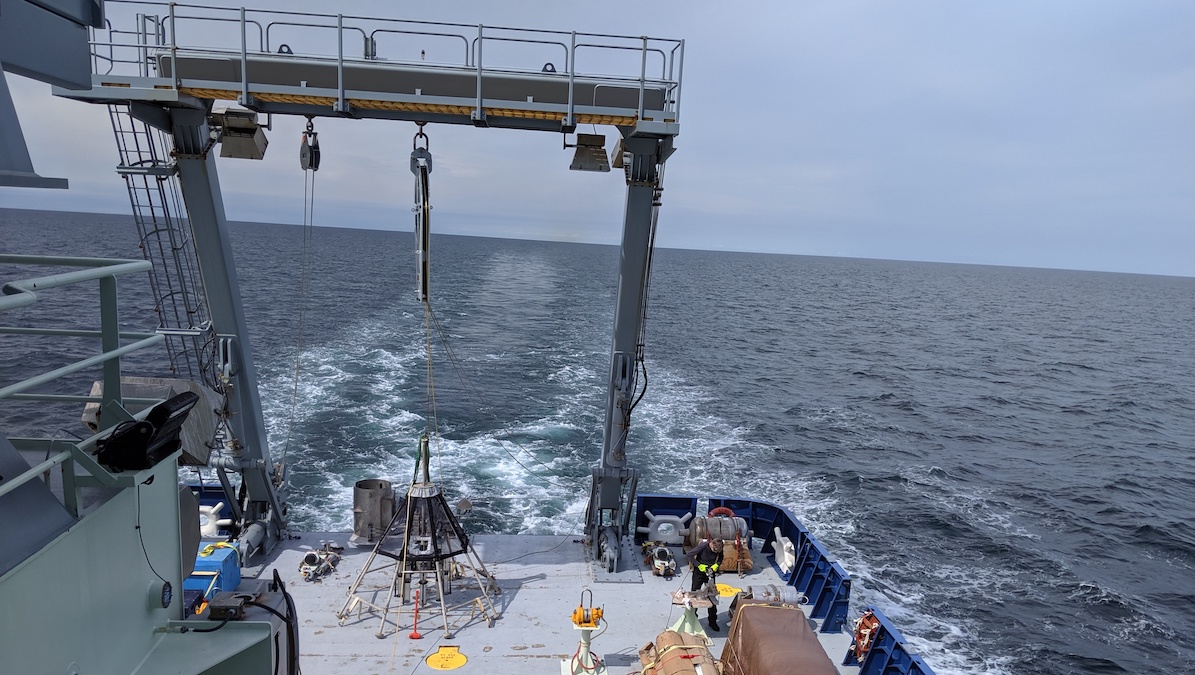

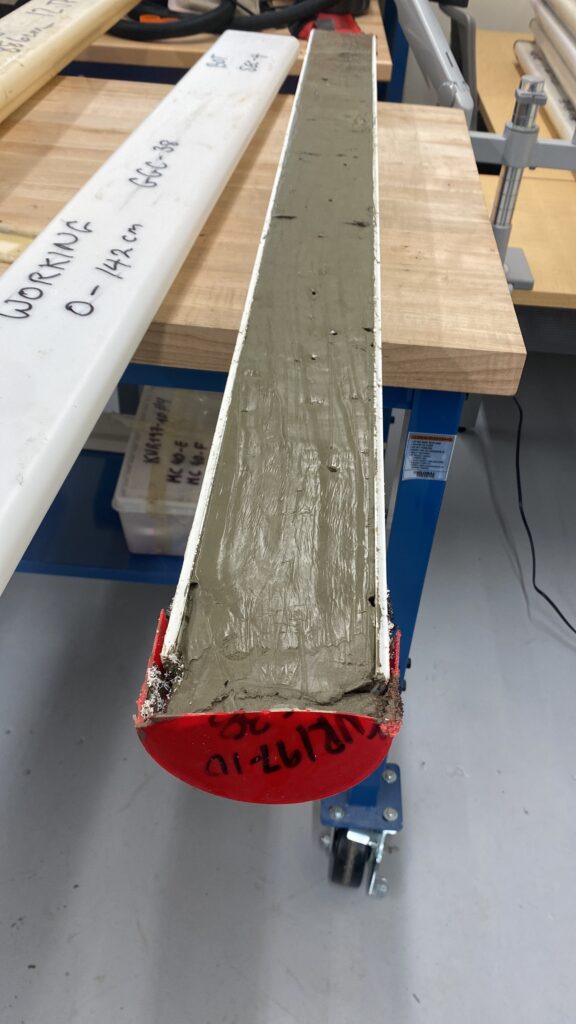

This unusual time left behind unusual rocks: Rusty red iron formations that accumulated where continental glaciers met the ice-covered seas. To take snowball Earth’s temperature, the team devised a new way to use that iron as a thermometer.

Iron formations accumulate in water that’s rich in dissolved iron. Oxygen transforms the easily dissolved, greenish “ferric” form of iron into rusty red “ferrous” iron that stays solid. That’s why almost all iron formations are ancient, relics of a time before Earth’s atmosphere started filling with oxygen about 2.4 billion years ago, or from the more recent snowball Earth, when the seas were sealed under ice. Unable to soak up oxygen from the air or from photosynthesis, snowball Earth’s dark, ice-covered seawater drained of oxygen.

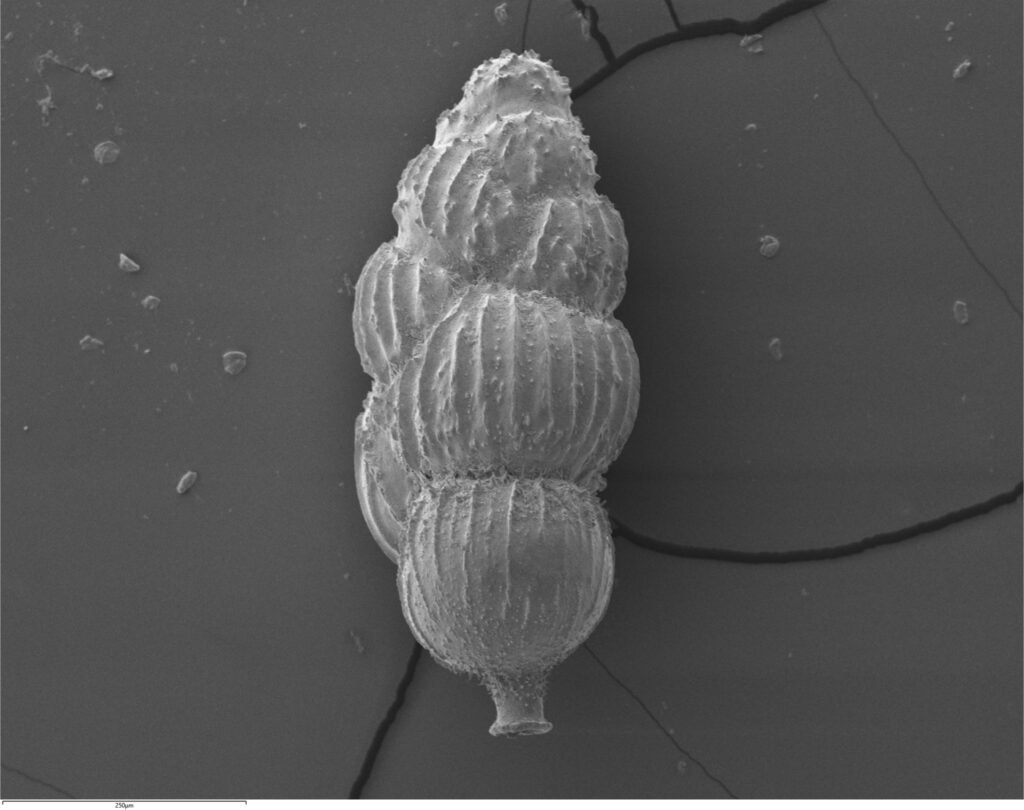

Iron-56 is the most common iron isotope, but lighter iron-54 rusts more easily. So when iron rusts in the ocean, the remaining dissolved iron is enriched in the heavier isotope. Over many cycles of limited, partial rusting—like what happened on the anoxic Archean Earth—this enrichment grows, which is why ancient iron formations contain isotopically very heavy iron compared to iron minerals that formed after Earth’s atmosphere and oceans filled with oxygen.

Snowball Earth’s iron is heavy, too, even more so than iron formations from the distant, preoxygen past. The researchers realized that temperature could be the explanation: Iron minerals that form in cold water end up istopically heavier. We don’t know exactly how hot it was when the ancient iron formations accumulated, but it was likely warmer than during snowball Earth, when glaciers reached the equator. Using a previous estimate of 25°C for the temperature of Archean seawater, the team calculated that the waters that formed the snowball Earth iron formations would likely have been 40°C colder.

“It’s a very interesting, novel way of getting something different out of iron isotope data,” said geochemist Andy Heard of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, who was not involved in the study. “It’s a funny, backwards situation to be in where you’re using even older rocks as your baseline for understanding something that formed 700 million years ago.”

In part because of that backward situation, Heard thinks the study is best interpreted qualitatively as strong evidence that seawater was really cold, but maybe not that it was exactly −15°C.

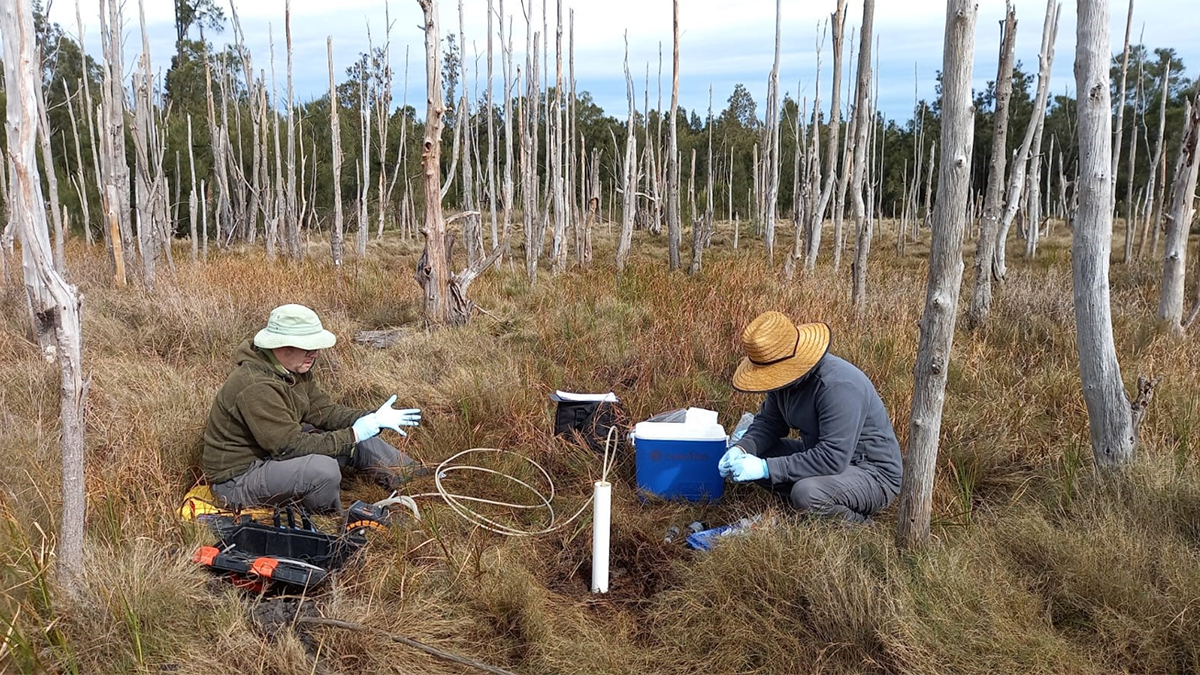

The team also analyzed isotopes of strontium and barium to determine that snowball Earth’s seawater was up to 4 times saltier than the modern ocean. Jochen Brocks of the Australian National University, who wasn’t involved in the study, said the researchers’ results align with his own salinity analysis of snowball Earth sediments from Australia based on a different method. Those rocks formed in a brine that Brocks thinks was salty enough to reach −7°C before freezing. Another group reaching a similar conclusion using different methods makes that extreme scenario sound a lot more plausible, he said.

“It was very cool to get the additional confirmation it was actually very, very cold,” he said.

—Elise Cutts (@elisecutts.bsky.social), Science Writer