Editors’ Vox is a blog from AGU’s Publications Department.

Coastal (tidal) wetlands are low-lying ecosystems found where land meets the sea, including mangroves, saltmarshes, and seagrass meadows. They are shaped by tides and support a mix of marine and terrestrial processes. However, agricultural and urban development over the past century have drained, modified, or degraded many of these coastal wetland ecosystems and now require restoration efforts.

A new article in Reviews of Geophysics explores how subsurface hydrology and biogeochemical processes influence carbon dynamics in coastal wetlands, with a particular focus on restoration. Here, we asked the lead author to give an overview of why coastal wetlands matter, how restoration techniques are being implemented, and where key opportunities lie for future research.

Why are coastal wetlands important?

Coastal wetlands provide many benefits to both nature and people. They protect shorelines from storms and erosion, support fisheries and biodiversity, improve water quality by filtering nutrients and pollutants, and store large amounts of carbon in their soils. Despite covering a relatively small area globally, they punch well above their weight in terms of ecosystem services, making them critical environments for climate regulation, coastal protection, and food security.

What role do coastal wetlands play in the global carbon cycle?

Coastal wetlands are among the most effective natural systems for capturing and storing carbon.

Coastal wetlands are among the most effective natural systems for capturing and storing carbon. This stored carbon is often referred to as “blue carbon”. Vegetation in these ecosystems, such as mangroves, saltmarsh, and seagrass, take up carbon dioxide from the atmosphere through photosynthesis and transfer it to sediments through roots. These plants can store carbon 40 times faster than terrestrial forests. Because coastal wetland sediments are often waterlogged and low in oxygen, this carbon can be stored for centuries to millennia. In addition to surface processes, groundwater plays an important but less visible role by transporting dissolved carbon into and out of wetlands. Understanding these hidden subsurface pathways is essential for accurately estimating how much carbon wetlands store and how they respond to environmental change.

How has land use impacted coastal wetlands over the past century?

Over the past century, coastal wetlands have been extensively altered or lost due to human activities. Large areas have been drained, filled, or isolated from tides to support agriculture, urban development, ports, and flood protection infrastructure. These changes disrupt natural water flow, reduce plant productivity, and expose carbon-rich soils to oxygen, which can release stored carbon back into the atmosphere as greenhouse gases. In many regions, groundwater flow paths have also been modified by drainage systems and groundwater extraction, further altering wetland function. As a result, many coastal wetlands have shifted from long-term carbon sinks to sources of emissions.

How could restoring wetlands help to combat climate change?

Restoring coastal wetlands can help combat climate change by re-establishing natural processes that promote long-term carbon storage.

Restoring coastal wetlands can help combat climate change by re-establishing natural processes that promote long-term carbon storage. When tidal flow and natural hydrology are restored, wetland plants can recover, sediment accumulation increases, and carbon burial resumes. Importantly, restoration can also reconnect groundwater and surface water systems, helping stabilize (redox) conditions that favor carbon preservation in sediments. While wetlands alone cannot solve climate change, they offer a powerful nature-based solution that delivers climate mitigation alongside co-benefits such as coastal protection, biodiversity recovery, and improved water quality. Getting restoration right is key to ensuring these systems act as carbon sinks rather than sources.

What are the main strategies being deployed to restore coastal wetlands?

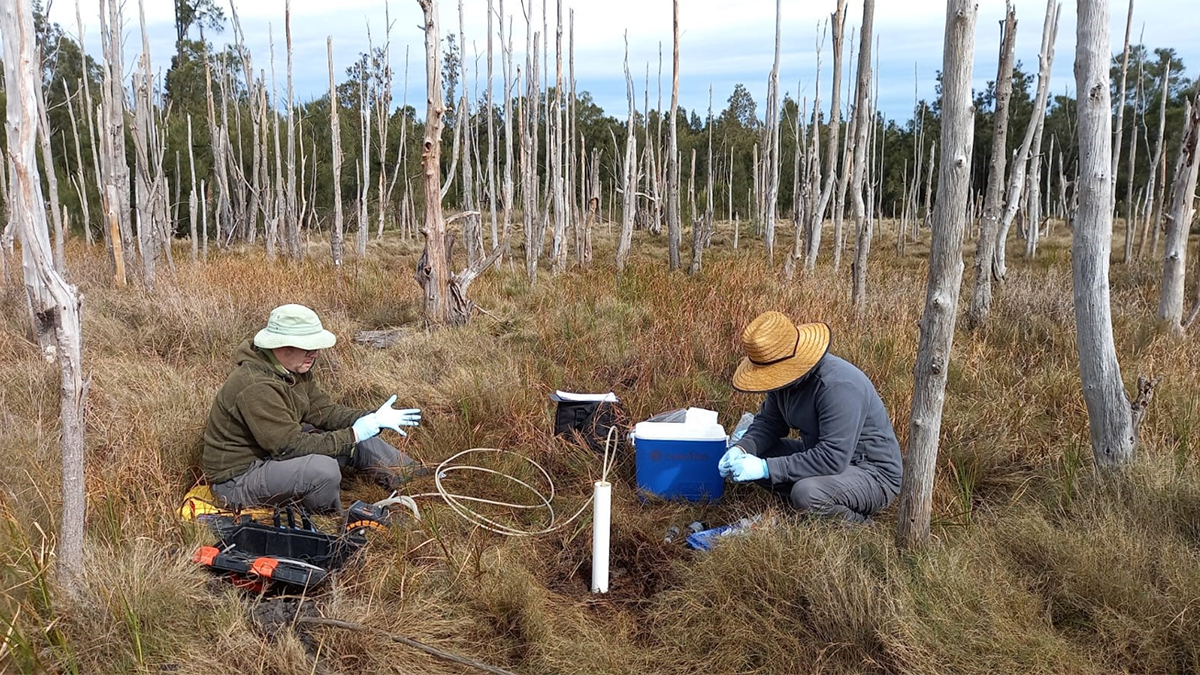

Common restoration strategies include removing or modifying levees and tidal barriers, reconnecting wetlands to natural tidal regimes, re-establishing natural vegetation through improving the hydrology of the site, and managing sediment supply. Increasingly, restoration projects are recognizing the importance of subsurface processes, such as groundwater flow and salinity dynamics, which strongly influence vegetation health and carbon cycling. Successful restoration requires site-specific designs that consider hydrology, geomorphology, and long-term sea-level rise.

What are some remaining questions where additional research efforts are needed?

Despite growing interest in wetland restoration, major knowledge gaps remain. One key challenge is quantifying how groundwater processes influence carbon storage and greenhouse gas emissions across different wetland types and climates. We also need better long-term measurements to assess whether restored wetlands truly deliver sustained carbon benefits under rising sea levels and increasing climate variability. Finally, integrating hydrology, biogeochemistry, and ecology into predictive models remains difficult but essential. Addressing these gaps will improve carbon accounting, guide smarter restoration investments, and strengthen the role of coastal wetlands in climate mitigation strategies.

—Mahmood Sadat-Noori (mahmood.sadatnoori@jcu.edu.au; ![]() 0000-0002-6253-5874), James Cook University: Townsville, Australia

0000-0002-6253-5874), James Cook University: Townsville, Australia

Editor’s Note: It is the policy of AGU Publications to invite the authors of articles published in Reviews of Geophysics to write a summary for Eos Editors’ Vox.