The rights of Nature: A new paradigm

Does Nature have inalienable rights just as humans do? This is what the rights of Nature paradigm stands for, marking a radical departure from the assumption that Nature is property under the law. The idea of rights for Nature stems from legal philosophy and political science. Partially, it is a product of the concept deep ecology, developed by the Norwegian philosopher Arne Næss. Deep ecology is based on an ecocentric worldview, which argues that the well-being of non-human life on Earth has value in itself, independent of any instrumental use by humans.

The application of the ‘rights of Nature’ in practice refers to granting legal rights or legal personhood for Nature as a whole or for categories of natural entities such as all rivers and ecosystems. These new rights have been acknowledged in local, national, and constitutional laws. Prominent examples include Ecuador’s constitutional recognition of rights for ‘Nature, or Pacha Mama’, Bolivia’s national Law of the Rights of Mother Earth, New Zealand’s Whanganui River Claims Settlement, and court decisions such as the Bangladesh Supreme Court’s recognition of rights for rivers and the Colombian Constitutional Court’s and Colombian Supreme Court’s recognitions of rights for the Atrato River and Amazon ecosystem.

Meanwhile, in Europe, shaped more by anthropocentric and rationalist traditions, interest in Rights of Nature has also grown steadily, partially thanks to a growing number of European scholars interested in the framework. The European Parliament and the European Economic and Social Committee also commissioned studies on the topic, resulting in reports such as Towards an EU Charter of the Fundamental Rights of Nature (2020) and Can Nature Get It Right? (2021), which helped carry the discussions into the European policy space.

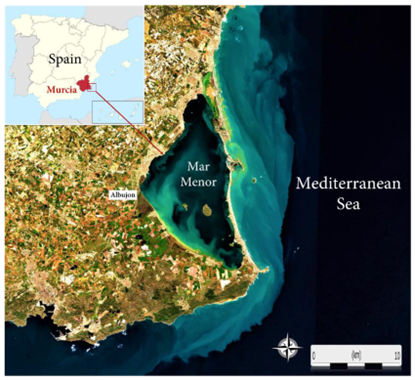

There were also attempts at the regional and national level to grant rights of nature to various ecosystems in EU countries such as the Netherlands, France, Sweden, and Switzerland, without immediate success. Finally, this changed in September 2022, when Spain recognised the Mar Menor lagoon as a legal entity, granting it legal personhood under the Rights of Nature framework. This landmark decision made the Mar Menor the first ecosystem in Europe to be awarded such status – an important moment for environmental governance in Europe. Eventually, in November 2024, Spain’s Constitutional Court upheld the Mar Menor Act of 2022 as constitutional. This ruling was the first in the EU to establish Rights of Nature at the constitutional level.

What happened to the Mar Menor?

Source: Caballero, Isabel & Roca Mora, Mar & santos-echeandia, Juan & Bernárdez, Patricia & Navarro, Gabriel. (2022). Use of the Sentinel-2 and Landsat-8 Satellites for Water Quality Monitoring: An Early Warning Tool in the Mar Menor Coastal Lagoon. Remote Sensing. 14. 2744. 10.3390/rs14122744.

Located in the province of Murcia in southeastern Spain, the Mar Menor is the largest saltwater lagoon in Europe. It is separated from the Mediterranean Sea by a sandy barrier with limited water exchange, creating a confined hypersaline environment. The lagoon’s high salinity supports its rich biodiversity, including abundant macrofaunal species, diverse fish populations, and habitats vital for nesting, migration, and wintering of aquatic birds. The lagoon and its surrounding Mediterranean coastline are also under protection by various international mechanisms, including designation as a Ramsar site and inclusion in the EU Natura 2000 Network under the Habitats and Birds Directives.

The Mar Menor’s drainage basin, Campo de Cartagena, is among the most productive and profitable agricultural regions in Europe. Known as the “vegetable garden of Europe”, around 70 percent of agricultural production from the region is exported. This is owed to the dramatic increase of water, fertiliser and pesticide use since 1970s, some of it through illegal irrigation practices. Alongside agriculture, decades of mining, tourism-driven urbanisation, and inadequate sewage management have contributed to severe pollution and ecological degradation of the lagoon.

The tipping point came in 2016, when the lagoon’s once-pristine waters collapsed into a green soup. This extreme eutrophication event was triggered by high levels of phosphates and nitrates in the water, which fuelled massive blooms of algae. The algae blocked sunlight and depleted oxygen levels, suffocating marine life; an estimated 85 percent of the lagoon’s vegetation was lost. Further collapses followed in 2019 and 2021, with more than five tonnes of dead fish washing ashore.

Scientists had long warned about the pollution of the Mar Menor, yet the regional government of Murcia followed a hands-off approach. Since taking power in Murcia in 1995, the right-wing Popular Party (PP) systematically dismantled environmental protections. They repealed the 1987 regional law protecting the lagoon, which had been passed by the preceding Socialist government, and repeatedly disregarded key environmental rules like the EU Nitrates and Habitats Directives. This political inaction coincided with agricultural businesses illegally dumping waste into the Mar Menor. This unchecked pollution served as a major environmental blow, as it devastated local life and severely damaged the lagoon’s natural ability to recover.

Source: https://www.boell.de/en/2025/02/05/mar-menor-europes-first-ecosystem-legal-personhood by Silvia de la Rosa

Popular legislative initiative and the legal personhood of Mar Menor

The ecological catastrophes sparked mobilisation in Murcia as well as other cities across Spain in 2019. At the forefront was Teresa Vicente Giménez, a professor of philosophy of law at the University of Murcia, who specialised in the Rights of Nature paradigm. With her students, she explored the possibility of granting rights to the Mar Menor. They concluded that the most efficient way of realising this was through a “Popular Legislative Initiative” which is a participatory democratic mechanism in Spain that allows citizens to propose a new law if they gather at least 500,000 signatures. In July 2020, Vicente launched the initiative with the support of NGOs campaigning for the preservation of the lagoon. Their campaign managed to collect around 640,000 signatures despite COVID-19 lockdown conditions. What began as an academic proposal turned into a powerful grassroots mobilisation, forcing the government to respond to the worsening crisis of the Mar Menor. On 5 April 2022, the Spanish Congress of Deputies approved the PLI, granting the lagoon legal status. The law was finalised in September 2022, and in 2024 the Constitutional Court upheld its validity.

The law enshrines the rights of the Mar Menor ecosystem to exist and evolve naturally, to be restored and protected, and to maintain the resilience of both the lagoon and its basin. Restoration efforts also envision a re-naturalisation of the Campo de Cartagena, including a transition to organic agriculture and livestock farming. In practice, as Teresa Vicente Gimenez and Eduardo Salazar explain, the law established three bodies of guardianship to represent the Mar Menor: a Committee of Representatives, a Monitoring Commission, and a Scientific Committee. The Committee of Representatives brings together three members of the General State Administration, three from the Autonomous Community, and seven citizens, with the task of proposing measures to benefit the lagoon. The Monitoring Commission is composed of representatives from the riverside and basin municipalities, elected by their respective City Councils, and is primarily responsible for defending the lagoon’s interests. The Scientific Committee, made up of scientists and independent experts on the Mar Menor, provides advice to the other two bodies and assesses the ecological status of the lagoon. Importantly, the law enables any citizen or legal entity to file lawsuits on behalf of the Mar Menor to enforce its rights.

How is the Mar Menor today?

Although some measures like water filtration and monitoring have been implemented, the situation of the Mar Menor is still fragile. The committees in charge of protecting the lagoon were only formed in May 2025, and the most significant legal challenge on the docket is scheduled for May 2026, when Mar Menor will appear for the first time as a claimant against an agricultural company accused of illegally discharging wastewater in the lagoon. The Mar Menor case also demonstrates the crucial role of geoscientists in implementing Rights of Nature frameworks in practice, such as the importance of the Scientific Committee in the Mar Menor Act in monitoring ecological health and guiding restoration. Yet, ultimately, it is the combination of ecological consciousness and sustained bottom-up democratic pressure that can turn the recognition of Rights of Nature into a victory for science-informed policy.

What does this entail for the EU?

The EU can be said to already have one of the world’s most comprehensive environmental governance frameworks. As stated above, the Mar Menor has already been under protection by the Birds Directive (2009/147/EC352) and the Habitats Directive (92/43/EEC). Therefore, some could argue that the Rights of Nature paradigm does not have an added value for the existing frameworks in the EU; since any alternative governance framework faces the same challenges as the existing schools of thought, eventually, they are all enforced by humans within existing political systems.

Here, it is important to note that legal personhood is not a magic wand that instantly fixes the institutional weakness and political inertia. Nevertheless, the Rights of Nature paradigm is valuable for offering us a new way of thinking about Nature. This includes significant potential for enhancing environmental liability. A relevant EU-level framework is the Environmental Liability Directive (2004/35/EC), which sets out a liability regime for environmental damage based on the ‘polluter-pays’ principle. The proponents of the Rights of Nature paradigm criticised the Directive for having a restrictive scope in terms of the damaging activities and calling for a burden of proof for environmental damages, as well as the wide room for derogation. In the case of this Directive, the Rights of Nature thinking has the potential conceptualise responsibility and accountability differently. For example, following the rights that were granted to the Mar Menor, the corporations could face claims for violating an ecosystem’s right to exist and evolve naturally, leading to more sensitive targets for ecosystems. This Directive is only one example of how an EU-level directive could be framed in a fundamentally different way thanks to the Rights of Nature paradigm, since it introduced new layers of accountability that transcend current governance frameworks.

Deutsch (Google Translate):

Die Rechte der Natur: Ein neues Paradigma

Besitzt die Natur ebenso unveräußerliche Rechte wie der Mensch? Dafür steht das Paradigma der Naturrechte. Es markiert eine radikale Abkehr von der Annahme, Natur sei Eigentum des Rechts. Die Idee der Naturrechte entstammt der Rechtsphilosophie und der Politikwissenschaft. Sie ist teilweise ein Produkt des Konzepts der Tiefenökologie, das der norwegische Philosoph Arne Næss entwickelte. Die Tiefenökologie basiert auf einer ökozentrischen Weltanschauung, die davon ausgeht, dass das Wohlergehen nichtmenschlichen Lebens auf der Erde einen Wert an sich hat, unabhängig von jeglicher instrumenteller Nutzung durch den Menschen.

Die praktische Anwendung der „Rechte der Natur“ bezieht sich auf die Gewährung von Rechtsansprüchen oder Rechtspersönlichkeit für die Natur als Ganzes oder für Kategorien natürlicher Einheiten wie Flüsse und Ökosysteme. Diese neuen Rechte wurden in lokalen, nationalen und verfassungsmäßigen Gesetzen anerkannt. Prominente Beispiele hierfür sind die verfassungsmäßige Anerkennung der Rechte an der „Natur“ oder „Pacha Mama“ in Ecuador , das nationale Gesetz über die Rechte von Mutter Erde in Bolivien , die Beilegung der Schadensregulierung im Zusammenhang mit dem Whanganui-Fluss in Neuseeland sowie Gerichtsentscheidungen wie die Anerkennung der Rechte an Flüssen durch den Obersten Gerichtshof Bangladeschs und die Anerkennung der Rechte am Fluss Atrato und dem Amazonas-Ökosystem durch das kolumbianische Verfassungsgericht und den Obersten Gerichtshof Kolumbiens.

Inzwischen ist auch im stärker von anthropozentrischen und rationalistischen Traditionen geprägten Europa das Interesse an den Rechten der Natur stetig gewachsen, was teilweise darauf zurückzuführen ist, dass sich immer mehr europäische Wissenschaftler mit diesem Rahmenwerk befassen. Auch das Europäische Parlament und der Europäische Wirtschafts- und Sozialausschuss gaben Studien zu diesem Thema in Auftrag, aus denen Berichte wie „ Auf dem Weg zu einer EU-Charta der Grundrechte der Natur“ (2020) und „Kann die Natur es richtig machen?“ (2021) hervorgingen , die dazu beitrugen, die Diskussionen in den europäischen Politikraum zu tragen.

Es gab auch Versuche auf regionaler und nationaler Ebene, verschiedenen Ökosystemen in EU-Ländern wie den Niederlanden, Frankreich, Schweden und der Schweiz Rechte der Natur zuzusprechen, jedoch ohne unmittelbaren Erfolg. Dies änderte sich schließlich im September 2022, als Spanien die Lagune Mar Menor als juristische Person anerkannte und ihr im Rahmen des Rahmenwerks der Naturrechte Rechtspersönlichkeit verlieh. Diese wegweisende Entscheidung machte das Mar Menor zum ersten Ökosystem in Europa, dem ein derartiger Status zuerkannt wurde – ein wichtiger Moment für die Umweltpolitik in Europa. Im November 2024 bestätigte das spanische Verfassungsgericht schließlich die Verfassungsmäßigkeit des Mar Menor-Gesetzes von 2022. Dieses Urteil war das erste in der EU, das die Rechte der Natur auf Verfassungsebene festschrieb.

Was ist mit dem Mar Menor passiert?

Quelle: Caballero, Isabel & Roca Mora, Mar & santos-echeandia, Juan & Bernárdez, Patricia & Navarro, Gabriel. (2022). Einsatz der Satelliten Sentinel-2 und Landsat-8 zur Überwachung der Wasserqualität: Ein Frühwarnsystem in der Küstenlagune Mar Menor. Fernerkundung. 14. 2744. 10.3390/rs14122744.

Source: https://www.boell.de/en/2025/02/05/mar-menor-europes-first-ecosystem-legal-personhood by Silvia de la Rosa

Der Fall Mar Menor ist der erste Fall, in dem die Rechte der Natur in einer Verfassung verankert wurden. Es ist jedoch wichtig zu bedenken, dass auf verschiedenen Ebenen innerhalb der EU bereits einige Anstrengungen unternommen wurden. Die Auswirkungen dieser Mentalitätsverschiebung weg von einer menschenzentrierten Naturperspektive werden wir möglicherweise nicht sofort sehen. In der EU, wo die Strukturen für die Umweltpolitik bereits gut etabliert sind, könnte sich das Paradigma der Rechte der Natur jedoch in naher Zukunft positiv auswirken.

The Mar Menor case is the first case where the Rights of Nature was realised in a constitution, however, it is important to remember that some effort has already been made at different levels within the EU. We might not see the implications of this mentality shift away from a human-centred perspective on Nature immediately; however, in the EU, where the structures for environmental governance are already well-placed, the impact of the Rights of Nature paradigm could be productive in the near future.

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen